This week’s posts are an attempt to understand the influence of parenthood on poetic practice. How do these (sometimes conflicting, it feels!) vocations inform one another? How can the reading habits of the very young help us become better writers? Better readers? And what can poetry teach us about parenting?

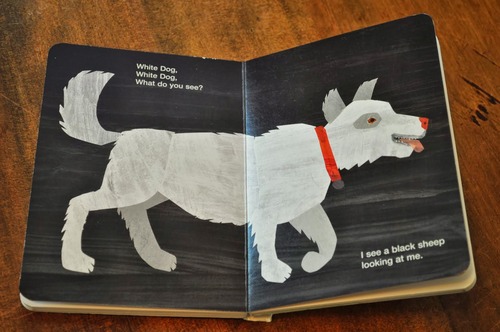

Recently, my daughter has begun spotting “Dog” everywhere. In books, during walks, embroidered on decorative pillowcases at Anthropologie (no, that’s a fox, darling…). She points, mouth puckered into a little “o” of discovery, grunts “ohh— ohh—.” We think this means “Woof, woof,” which makes sense, since now that I’m a parent, I’m weirdly incapable of pointing out any fish, fowl, or land animal without also asking, “What does the _____________ say?”

When “reading,” she searches out pictures of dogs and will flip pages furiously until she finds one. “Ohh, ohh.” Are we so different, as poets? We’re drawn to recognizable forms, images that haunt. The hand pressed against the windowpane. The stained coffee mug in the sink. These motifs emerge, ghostlike, everywhere in our poems. I recently taped the pages of a manuscript I’ve been revising up on a wall, only to see the word “face” appear over and over again. An unnerving experience, considering that it was never my intention to write a project about the human face. Yet, there it is. Face, face.

What haunts us, draws us back? Dog. Dog. Soon we’re searching for it everywhere, spotting it in places that bear only the remotest likeness. Teddy? Panda? Close enough. This is the poet-mind that latches on to a form and, once recognizing it, fixates and will not let go. Whether we’re aware of it or not, we’re often claimed by some cadence or unusual image, which holds on until it’s through.

It’s possible that we’re not that far removed from our infant selves: pointing, naming. Ohh! Ohh! Our poems are sparks of recognition, moments of familiarity in the midst of life’s bewildering muddle. Or, they’re attempts to render the unfamiliar in terms we can understand, to build a linguistic apparatus by which we can make (sometimes mistaken) sense of the world. That creature there—black and white patches on its face, a striped tail— Dog? No, darling, that’s a raccoon… But what matters most is the mind at work, the act of perception. The art’s in the articulation.

Mia Ayumi Malhotra is a 2012 Kundiman Fellow and the mother of a ten-month-old. She teaches and lives in the Bay Area. Visit her website at miamalhotra.com.