For each day of National Poetry Month one of our fellows will explore the breadth of poetry in three ways: through a question from another fellow, through a poem and through a writing prompt, #writetoday.

[QUESTION]

Monica Ong asks, Time is limited, yet nowadays there is a limitless amount of great literature and art one can take in. What is your criteria for choosing what or whom to read, in terms of growing as a poet?

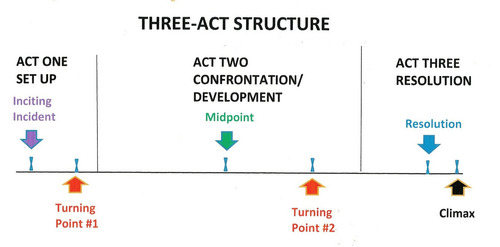

Michelle Penaloza answers, I am a bit promiscuous; I don’t know that I have any criteria other than “whatever holds my interest.” On my nightstand: Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do by Claude M. Steele, The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke, the Magic Shows issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, and Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s Lucky Fish. I often discover what and whom I read through friends, writerly or not. I have a subscription to The New York Review of Books, which adds lots of books to my constantly growing list. Sometimes random things on the internet lead me to new poets and new books; I have a bookmarks tab that’s just labeled READ THESE for my running list of stuff I want to read. Basically, I say yes to almost everything; my criteria becomes discriminating once I’ve gotten started with something. The library is my dear friend. Also, [the visual below] might illustrate my answer this question.

[POEM]

LESSONS IN COMMUNICATION

If you enter a house through the window

instead of the door, a ghost will follow you.

If two dogs bark at night, you know the ghost

wants to watch Doctor Zhivago, cry, and steal

all of your wheat toast, your Earl Gray, and your butter.

Should you suddenly feel a weight upon your chest,

the ghost would like to speak with you about its concerns

regarding your late night habits—you eat dinner too late

in the evenings, you smack your gums while watching television,

you are a terrible judge of character (really, the men you

bring home), you smoke too much, and you haven’t been to mass

in years. Also, you no longer make an effort to speak to the dead.

This, the ghost will say, is very disappointing.

To hush a ghost, you must spin counter clockwise three times.

Hold your palms upward and whistle Mancini’s “Moon River.”

You can never really make a ghost hush, but if you stand within

a circle of salt, knock three times upon a mirror and light a single

white candle, you can manage a ghost’s moaning, order it

to stay in the starlight, to stay on the other side of the windows’ glass.

When you get lonely, you can press your ear upon the darkness and listen:

cricketsbittermelongoldleafbullsbreathfoxglovewhatsightreefallrainclouddustdustdust

First published in The Weekly Rumpus.

[BIO]

Michelle lives in Seattle, hard at work on her current project, landscape / heartbreak; also, this brings her great joy.

![For each day of National Poetry Month one of our fellows will explore the breadth of poetry in three ways: through a question from another fellow, through a poem and through a writing prompt, #writetoday.

[QUESTION]

Brynn Saito asks, Do you believe …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/512f1afce4b08130491e0fe5/1427698920425-BDM78CTPA71MSTNHOTNP/image-asset.jpeg)